Jan Baptist was 20 years old when he died in late September 1915, not far from the Yser Front in Oostkerke. A mere 45 kilometres from the place he was born. The First World War had only just entered its second year. The cause of his death, other than the consequences of a horrifying war, is unknown.

The same Cloth Hall and the same market that were rebuilt after the war in their old style. After all, there was nothing left of Ypres. Clouds float past hurriedly and that is just as well. Remembering a war in the sunshine is cruel, it’s as if it secretly came good. Perishing cold is better.

Before I drive into the city, I make a stop at the White House Cemetery, St. Jean-les-Ypres. It is one of the more than 150 gaping wounds left by the Great War in the landscape of West Flanders. The scrubbed white gravestones are the last witnesses of the bloody trench warfare. In the distance, cranes and two horses – one white and one brown – stare over the fence at the graves. Poppies, the symbol of this war, bloom in exuberant red amongst the immaculate white.

In Flanders Fields

In the year that Jan Baptist died, the Canadian John McCrae, who did not survive the war either, wrote a poem about those poppies: In Flanders Fields. The title would later become the name of the war museum in Ypres.

“In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing,

fly Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn,

saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved,

and now we lie In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.”

What is actually our connection with the First World War? I found myself wondering in the car on the way from the Netherlands to Ypres. For Dutch people, it’s a war from long ago. A war that is not preserved in the collective consciousness like the Second, where every father or grandpa was reputed to have carried out a heroic act of resistance. The Netherlands were neutral. They did sufficient receiving Belgian refugees and, somewhat amazingly for a neutral country, granting asylum to the warmongering German Kaiser Wilhelm.

Schlieffen plan

But in Belgium, which was overrun by German troops as part of the Schlieffen plan to reach Paris, this war is omnipresent.

A war where men were still men and marched off singing to the front. Who did what they were told, even if they didn’t understand the French-speaking officers. For anyone who later decided to call it a day, overcome by shell shock or struck by the perception that the war was hardly ennobling for the soul, death awaited anyway. Carried out at daybreak at the execution pole, like the one that can still be seen in Poperinge. In the condemned cell, the desperate prisoners etched their last thoughts into the wall. War was not for cowards, that much was clear.

The world is full of coincidences. And that is especially true of the First World War. There was once a boy by the name of Gavrilo Princip. A lad the same age as Jan Baptist, who conceived the plan in Sarajevo to shoot the Austrian-Hungarian crown prince and his wife dead during a state visit. It’s little short of a miracle that the murder succeeded, because the attack, just like its prevention, depended on a series of trivialities.

First World War

That murder was the opening move in what would turn into the First World War a few weeks later and the death of Jan Baptist, a Belgian boy 1800 kilometres further away, who was as yet unaware that his days – just like those of millions of other boys – were numbered.

In the In Flanders Field Museum, located in the Cloth Hall, I am given a poppy bracelet and wander for hours through four years of devastation, death and destruction. I listen to the stories of English Gregg Nottle, Belgian Karel Lauwers, French Maurice Laurentin and German Kurt Zemisch, who sang Silent Night together and exchanged presents during Christmas night in the trenches in 1914.

A few days later they picked up their weapons once again to shoot at each other. That is what insanity looks like. Shortly before I leave the museum, I hold my poppy bracelet up to a signal.

The computer indicates how many people with my family name died in the war, provided I filled in my name at the entrance. A single name appears on the screen: Jan Baptist Alphonse de Bundel. I look at it in amazement. There is a De Bundel who died in that accursed war. That makes it personal.

Adinkerke

Damn! Why did the museum not give out the names immediately at the entrance? Then I could have walked through the war together with Jan Baptist. I could have lingered by the stories of the refugees who fled from Ostend to Adinkerke and even further, in the hope of reaching England. I could have asked him why he didn’t flee, instead of ending up dead in Adinkerke.

Jan Baptist Alphonse de Bundel. I pick up my pen and write my name underneath his.

An Albertine Alfonsine de Bundel.

Where was Jan Baptist at Christmas 1914 when the young men sang together? Did he celebrate Christmas in a rat-infested trench? Or was he at home, convinced that the war surely would not last much longer?

As soon as I’m outside, I send my father an e-mail. Did we have a Jan Baptist in the family? My father directs me to my nonkel (Belgian word for uncle) who is in charge of the family tree.

I drive to Poperinge to Talbot House, where the stressed-out British soldiers, regardless of rank, could rest and relax. Where did Jan Baptist rest? Did he read a book in the garden, like the soldiers here? Did he despair just like the many British men in this house and turn to God in a church that was not yet shot to pieces?

Cabour Hospital

I read that many of the soldiers who lie buried in Adinkerke came from Cabour hospital. Founded in early 1915, thousands of servicemen were treated here up until 1917 for what was left of the parts of their bodies that were shot or blown up. I try not to think about amputations carried out under primitive conditions on boys tanked up on alcohol.

I send the museum’s Knowledge Centre an e-mail with a request for more information about Jan Baptiste. Then I walk to the place of execution and the death cell for soldiers accused of cowardice. Erwin Mortier wrote about the fear and madness of that last night.

With a piece of white paper pinned to his chest, the condemned man waited for the boys from his own battalion to open fire on him. “Don’t aim at me lads, aim at the white linen on my chest,” wrote Mortier in the verse placed next to the execution pole.

An e-mail arrives. My great-grandfather’s brother Frederik was called Jan Baptist. A date of birth is being looked for. I notice that I’m holding my breath.

Last Post

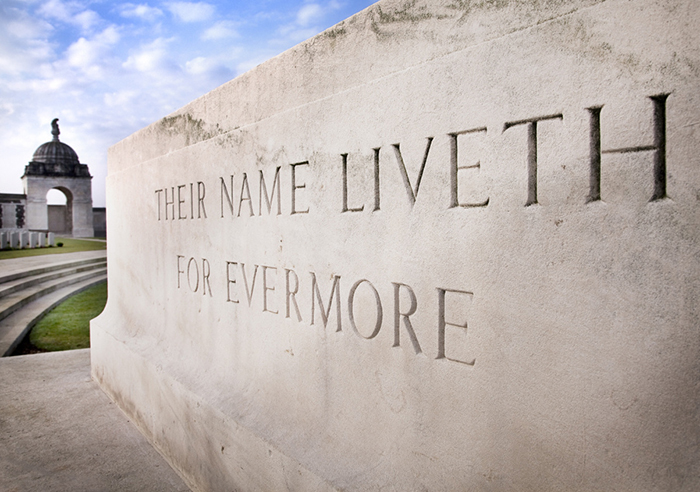

In the evening, back in Ypres, I attend the Last Post, the salute of honour that has been sounded every evening since 1928 under the Menin Gate. The gate is filled with the names of more than 50,000 British officers and men whose bodies were never identified or found.

I think about Jan Baptist. Was he my great-great-uncle? I just can’t see the 20-year-old boy as an old man. Death has made him young for ever.

The following morning I receive an e-mail. From the Knowledge Centre attached to the museum. Unfortunately, there is very little known about the fallen Jan Baptist. However, they can tell me that he was from Meulenbeke, in West Flanders.

That is bad news because, for generations, our family did not extend any further than Erembodegem. It may be the proud village of the writer Louis Paul Boon, but it’s undeniably in East Flanders.

“If I want”, the lady from the knowledge centre writes, I can submit a request to inspect the military dossier at a notary’s office in Brussels. “But”, she warns: “it can take a while before you receive an answer, they are inundated with requests at the moment.”

Doubt

And then the e-mail arrives from my nonkel that removes any doubt. Great-grandfather’s brother Frederik was born in Erembodegem in 1882 and died long after the First and even the Second World War in that same Erembodegem.

On the drive back to the Netherlands, I think about the introduction to the In Flanders Field Museum press file: “We want to tell the big story through the small stories of the people who were involved.” I think it’s time for me to visit Jan Baptist in Adinkerke.

Text: Anneke de Bundel – Images: Toerisme Ieper

Translation: Christine Gardner

This story was written at the invitation of Toerisme Vlaanderen & Brussel

Both story telling and photos kept me involved from start to finish. A wonderful rendering of such a sad, crazy and horrific time in history! Thank you!

Thank you Evelyn for your kind comments.